“I saw a building that said, ‘Self Storage,’ and I thought, ‘I wonder if my ego could possibly fit in just one unit.’”

– Jarod Kintz

I did pretty well in high school. I came close to getting straight As, was president of a couple of clubs, played on sports teams, and had a job. I was pretty sure that there was nothing that the world could put in front of me that I couldn’t tackle.

Then I went to West Point. It seemed like most of my friends there were class presidents, 3 sport stars, and valedictorians of their high schools. Whereas I had once been in a place where my performance was fairly remarkable, I was suddenly in a situation where I wasn’t one of the best/smartest/fastest/whatever around.

Furthermore, in classes, the academic powers that be sectioned off classrooms in academic performance order. Therefore, if you were in section 1 of a given class, you were in the top 25 or so out of the about 1,050 cadets in the class – assuming that it was a general curriculum course like physics or calculus. So, by looking at your section number, you knew exactly where you stood compared to all of your classmates. They also published your rankings in all three areas of cadet life: academic, physical, and military. All of this was important because your rank in your class determined whether or not you got your choice of branch (e.g., tanks, infantry, military intelligence, etc.) and choice of duty station after basic training.

If you were previously a high performing student in high school, then the transition to West Point could be quite a shock. The academics were much harder – everyone graduates with an engineering degree, so we got plenty of math and science thrown our way – and I had some exceptionally smart classmates. It would be easy to have that “not so bright” feeling when thrown up against people who were brilliant and athletically gifted.

Back in the 1960s, the University of Chicago’s James Davis noticed the same phenomenon happening across Ivy League schools. Students who were getting the “gentleman’s B” in Ivy League schools were subsequently not going after high-paying, respected careers because they felt like they weren’t doing all that well compared to their classmates.

What these students were forgetting was a pretty important piece of life advice.

They were capable enough to earn a B at an Ivy League school!

There are very few people in the world who excel enough in their studies to earn a spot into an Ivy League institution in the first place. Let’s say that only the top 2% of students could get into an Ivy League school (I have no idea if that’s accurate or not, by the way, but it’s probably close enough). If you finished with a 3.0 and were dead middle of your class at an Ivy League institution, that means that you’re still in the 99th percentile compared to your overall peer group.

Meanwhile, back at West Point, I was also well aware of the experiences my friends who weren’t at West Point were having that I was not. We’d exchange letters. Mine told of being hazed (deservedly so) or of not leaving post or of cold winters. My friends would write of sorority and fraternity parties, Spring Breaks, and the like. Civilian college life seemed hedonistic and exquisite compared to my sere existence.

At the same time the academics in the University of Chicago were studying Ivy Leaguers, Walter Runciman was studying social mobility among the English. In his study, he noted that people felt like they were deprived of something which they deserved if they met the following four conditions:

- A person didn’t have something

- He knew of other people who did have something

- He wanted it

- He believed it was possible to have that thing

Both of these studies defined aspects of the same psychological phenomenon: relative deprivation.

Relative Deprivation – Suffering Because Your Man Cave is Too Small

Monkey Brain loves to keep up with the Joneses. For those of you who are new here, Monkey Brain is what I call the limbic system – the prehistoric part of our brain that monkeys also have. Back when we were not so civilized, it was our limbic system that kept us alive, telling us to run away long before we could think “hey, that’s a woolly mammoth.”

When we were living in caves being awed by the discovery of fire, we hunted woolly mammoths in packs. It was important to Monkey Brain to be part of a good hunting group, because doing so gave him a better chance of catching dinner. Being left alone in the cold usually meant a quick demise.

So, when the group caught a woolly mammoth, members of the pack got their spoils. However, if Monkey Brain sensed that he’d worked just as hard as everyone else but didn’t get the choice filet mammothion au poivre, he’d feel real injustice, and feel like he was getting the raw end of the deal.

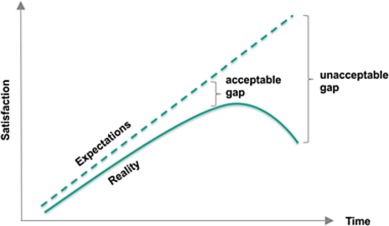

We still get that feeling today. When we see others who have a lifestyle that we think that we deserve or that we think they didn’t work to get, we feel slighted. That feeling is relative deprivation – feeling that someone who didn’t lift a finger to do anything in the world (like, say, reality TV stars) got all of the breaks and all of the spoils and here we are, hard-working honest people, so we deserve good things like Jimmy Choo shoes and man caves.

Experiencing relative deprivation could expose our wallets to some bad outcomes. We could listen to Monkey Brain tell tales of woe.

Monkey Brain: “YOU WORK HARD. YOU DESERVE NEW CORVETTE. SNOOKI HAS NICE CAR. YOU SHOULD HAVE ONE TOO.”

You: “Where’s the nearest dealer?”

It can also cause you to have feelings of attachment to your current lifestyle, particularly if you need to dial it back. Want to cut your cable? Monkey Brain will flood your prefrontal cortex – the thinking you – with images of a poor, suffering, bored-to-tears Future You who doesn’t have cable TV and is miserable. Relative deprivation works not just in comparing yourself to others who have more than you, but it can also work in comparing yourself to what you once had (or potentially would have once had if you’re trying to trim your spending), keeping you from making wanted or necessary changes in your life.

Relative deprivation also has an effect in causing you to have limiting beliefs in your career or in entrepreneurship. If you were chosen for a special R&D team of top performers and wound up being slightly below average in that group, it might keep you from looking for challenging positions later on in your career. If you are a part of a networking group that has entrepreneurs who run million dollar companies and you only have revenues of several hundred thousand dollars, you might start to get down on yourself because your company isn’t as big as the companies of your peer groups.

You may be at the very bottom of the top percentile in something, and instead of looking down at the remaining 99% of those who haven’t achieved your heights, you only look up at the 99% of people above you in that very small group.

Perspective is everything.

Relative deprivation happens when we have too narrow of a focus on the group of people to whom we compare ourselves. The more unrealistic the comparisons (such as comparing yourself to Snooki, unless you are Snooki), the harder the hit of relative deprivation is going to feel.

So, next time you feel like you don’t get something you deserve, remember, you have food. You have water. You have shelter. You live in a land of opportunity.

If you feel like you’re falling behind your peers, look outside of your peer group. Are you the dumbest kid at Harvard? That means you’re still pretty darn smart.

Have you ever fallen prey to relative deprivation? Let’s talk about it in the comments below!

Author Profile

- John Davis is a nationally recognized expert on credit reporting, credit scoring, and identity theft. He has written four books about his expertise in the field and has been featured extensively in numerous media outlets such as The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, CNN, CBS News, CNBC, Fox Business, and many more. With over 20 years of experience helping consumers understand their credit and identity protection rights, John is passionate about empowering people to take control of their finances. He works with financial institutions to develop consumer-friendly policies that promote financial literacy and responsible borrowing habits.

Latest entries

Low Income GrantsSeptember 25, 2023How to Get a Free Government Phone: A Step-by-Step Guide

Low Income GrantsSeptember 25, 2023How to Get a Free Government Phone: A Step-by-Step Guide Low Income GrantsSeptember 25, 2023Dental Charities That Help With Dental Costs

Low Income GrantsSeptember 25, 2023Dental Charities That Help With Dental Costs Low Income GrantsSeptember 25, 2023Low-Cost Hearing Aids for Seniors: A Comprehensive Guide

Low Income GrantsSeptember 25, 2023Low-Cost Hearing Aids for Seniors: A Comprehensive Guide Low Income GrantsSeptember 25, 2023Second Chance Apartments that Accept Evictions: A Comprehensive Guide

Low Income GrantsSeptember 25, 2023Second Chance Apartments that Accept Evictions: A Comprehensive Guide